For much of modern organizational history, “we didn’t know” functioned as a quiet but powerful shield. When incidents occurred - legal violations, reputational crises, security failures—leaders could credibly argue that the relevant information was unavailable, obscured, or unknowable at the time decisions were made.

That shield no longer holds.

In today’s environment, ignorance is not presumed innocent. It is interrogated. Courts, regulators, boards, and the public increasingly treat lack of awareness not as an unfortunate condition, but as a potential failure of governance, oversight, or judgment.

The question is no longer whether an organization knew.

It is whether it should have known.

The End of Plausible Ignorance

Plausible ignorance depended on two assumptions:

First, that meaningful risk signals were rare, slow, or difficult to obtain.

Second, that decision-makers could not reasonably be expected to detect weak or emerging threats before they manifested.

Both assumptions have collapsed.

Organizations today operate inside dense information ecosystems. Open-source intelligence, regulatory filings, social platforms, internal communications, vendor alerts, monitoring tools, and AI-driven summaries generate a continuous stream of signals. Risk no longer arrives unannounced. It accumulates, leaks, mutates, and often leaves a trace long before it becomes visible as an incident.

As a result, ignorance is no longer evaluated passively. It is examined as a condition that must be explained.

Awareness Has Become an Expectation, Not a Bonus

In prior eras, awareness was treated as an advantage. Organizations that detected problems early were praised for diligence. Those that did not were often excused.

Today, awareness is increasingly treated as a baseline expectation—particularly for organizations operating in regulated, high-exposure, or high-impact environments.

This shift is subtle but decisive. It reframes the standard entirely.

When regulators, litigators, or investigators ask what leadership knew, they are rarely satisfied with a simple negative. They probe for systems, processes, and judgment structures that should have surfaced the issue earlier.

The absence of awareness is no longer neutral. It is contextual.

The Rise of the “Should Have Known” Standard

“We didn’t know” fails when it collides with a harder question:

Given the available signals, was ignorance reasonable?

This standard is now applied retroactively and aggressively.

Investigators examine whether:

Signals existed but were ignored

Alerts were generated but deprioritized

Information was siloed or fragmented

Responsibility for interpretation was unclear

Decision-makers relied on tools without understanding limitations

In this framework, ignorance becomes a system outcome, not an accident. And system outcomes are assignable.

Information Abundance Has Raised the Bar

Ironically, the explosion of data and intelligence tools has raised expectations rather than lowered them.

When information was scarce, not knowing was understandable.

When information is abundant, not knowing requires justification.

Organizations now face a paradox: the more tools they deploy, the harder it becomes to argue that risk was undetectable. Feeds, dashboards, AI summaries, and monitoring platforms leave behind evidence of availability—even if interpretation was flawed.

In post-incident analysis, the question often becomes:

Why did this information not change behavior?

That question is far more dangerous than “why didn’t you have access?”

Delegated Awareness Is Not Delegated Responsibility

A common failure point emerges when organizations conflate outsourcing awareness with outsourcing accountability.

“We relied on the platform.”

“We relied on the vendor.”

“We relied on the automated system.”

Reliance does not equal responsibility transfer.

Decision-makers are increasingly expected to understand not only what systems produce, but what they cannot produce. Blind reliance on third-party tools or automated intelligence without human synthesis is now viewed as a risk decision in itself.

Delegated awareness without accountable interpretation creates a vacuum—one that is quickly filled during litigation, regulatory review, or reputational collapse.

Internal Signals Are the Most Dangerous to Ignore

Some of the most consequential “we didn’t know” defenses fail not because of external intelligence gaps, but because of ignored internal signals.

Internal communications, employee concerns, audit findings, compliance warnings, and behavioral anomalies are now treated as intelligence artifacts. When these signals exist—and they often do—the failure to interpret them carries significant weight.

Organizations are discovering that internal ignorance is harder to defend than external surprise.

Speed Has Eliminated the Grace Period

Another critical change: the collapse of the response window.

Previously, organizations could rely on a buffer between incident and scrutiny. Internal reviews could be conducted. Facts could be gathered. Messaging could be prepared.

That window has narrowed or vanished.

Digital communication, leaks, screenshots, and real-time narrative formation mean that explanations are evaluated while events are still unfolding. Claims of ignorance made under these conditions are immediately tested against available data—often publicly.

In this environment, delayed awareness is interpreted as structural failure, not timing.

Documentation Without Judgment Is Insufficient

Many organizations assume that documentation protects them: meeting notes, reports, dashboards, and summaries that show information existed.

But documentation now raises a more dangerous question:

If this information existed, why did it not lead to action?

What matters is not the presence of information, but the quality of judgment applied to it.

Who reviewed it?

What was questioned?

What assumptions were challenged?

What was escalated—and what was dismissed?

Without answers to these questions, documentation becomes evidence of missed opportunity rather than diligence.

The Collapse of the “Complexity” Excuse

Complex systems once provided cover. Decision-makers could plausibly argue that risk emerged from unforeseeable interactions or technical opacity.

That argument is weakening.

As complexity becomes normal, organizations are expected to build intelligence structures capable of operating within it. Claiming that a system was too complex to understand is increasingly interpreted as a failure of governance, not a mitigating factor.

If complexity is inherent, preparedness must scale with it.

From Ignorance to Defensible Judgment

What is replacing “we didn’t know” is not omniscience, but defensible judgment.

Defensible judgment demonstrates that:

Signals were actively sought

Information was synthesized, not merely collected

Uncertainty was acknowledged

Escalation thresholds were tied to consequence

Human accountability was preserved

This standard does not demand perfect foresight. It demands proportionate, documented reasoning under uncertainty.

Why This Shift Is Permanent

This change is not cyclical. It is structural.

Information environments will only become denser. AI will only accelerate synthesis. Scrutiny will only intensify. In that context, ignorance becomes harder to justify with every passing year.

Organizations that continue to rely on absence of knowledge as a defense are operating on an expired assumption.

The Role of Protective Intelligence

Protective intelligence exists precisely because awareness alone is insufficient.

It is designed to:

Identify meaningful signals amid noise

Interpret risk in context of consequence

Support judgment under pressure

Produce documentation that survives scrutiny

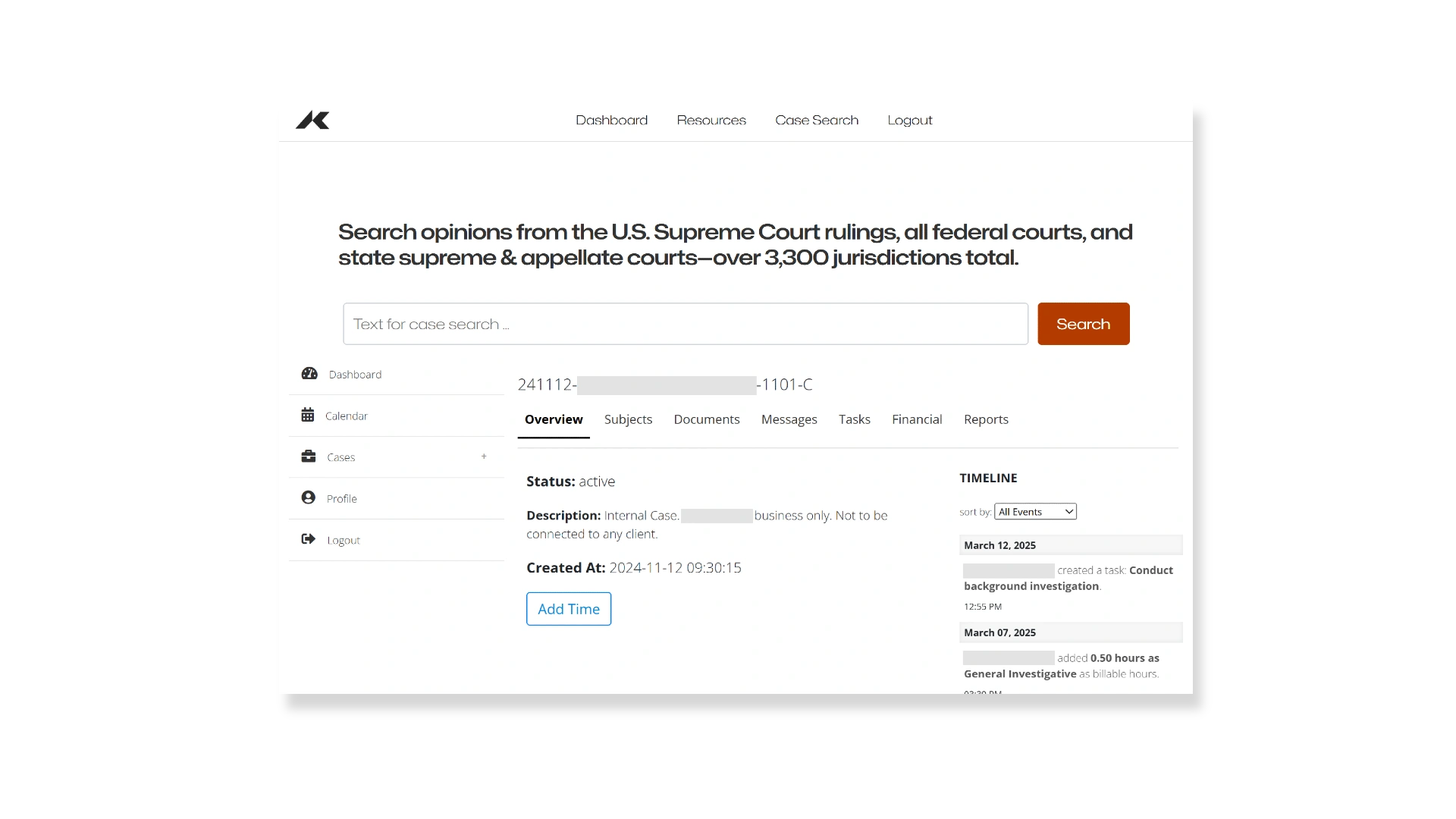

At Archer Knox, the focus is not on knowing everything, but on ensuring that leaders are never forced to explain why they knew nothing.

Conclusion

“We didn’t know” once implied innocence.

Today, it implies a question: Why not?

In modern risk environments, ignorance is no longer a condition—it is a decision outcome. And decision outcomes carry responsibility.

The organizations that endure will not be those with the most data or the loudest tools. They will be the ones that recognize a simple reality:

In a world saturated with signals, not knowing is no longer a defense. Judgment is.